Saudi Women Speak Out about The Driving Campaign

October 28, 2013 | Nadine El SayedTired of waiting, Saudi women decided to literally take the wheel into their hands and show authorities driving is their right to snatch, whether the state likes it or not.

Activists in Saudi Arabia launched a campaign urging women to take the wheel and drive themselves on October 26th in an effort to pressure authorities to lift the ban on women driving, a right they’ve been fighting for for decades. The campaign also gathered 17,000 signatures calling for the lift of the ban on driving as no articles in the Saudi law formally ban driving for women.

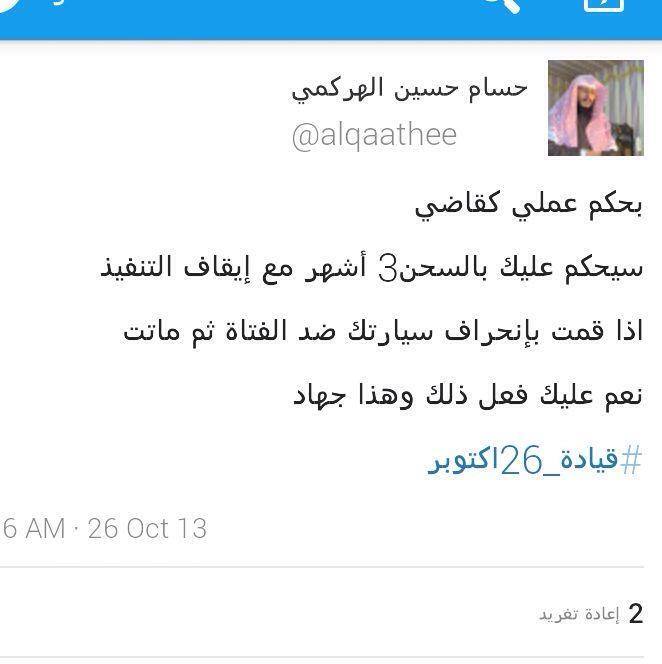

Despite threats from officials and conservative figures on the illegality of the actions the women’s rights groups call for, more than 60 Saudi women of different ages across the kingdom took the wheels on Saturday to show their insistence on the right to drive in one of the most successful protests for the right to drive in Saudi’s history. Campaign organizers say they received over 50 messages and 13 videos of women claiming they took the wheels in various parts of Saudi last Saturday.

“I support women’s driving for financial and economic reasons,” says television hostess and writer Ghada Mimi Aboud. “Unlike what many Arabs think, we’re not [all] rich, most of us are middle class. So I support it for the sake of millions of Saudi women who were hired to work in cities that are hundreds of kilometers away [from their homes] and might be paying one third of their salaries to drivers.“

Without a proper public transport system and a cultural stigma attached to women riding in taxis alone, middle class Saudi women are forced into hiring drivers who cost 1,200 Saudi Riyal (LE 2,204) to 1,700 Saudi Riyal (LE 3,122).

Aboud adds that the issue goes far beyond women’s rights and well into basic economic rights and a rule that forces women to spend hefty sums on transport. Lana Komsany echoes the same concerns about the financial costs this ban poses on women, which inevitably reflects on her freedom to work.

“I support the initiative a 100% because women in my country lack basic freedom and we are treated like second class citizens. This is a human rights issue and what is happening is inevitable […] women are fed up of not being taken seriously and they’re simply rebelling,” says Komsany. “I work and need to go to work everyday and drop my kids off to day care.”

Komsany tells the story of her mother who raised her kids alone and so without a man in the house, the family has always suffered from dishonest and harassing drivers they had to bare with because they couldn’t drive on their own. “Women who are widowed or divorced face the responsibility of driving around to fulfill errands and take care of the family without wasting money on drivers,” she adds.

Many protestors posted videos of themselves driving around the streets of Saudi Arabia, many of whom had male relatives accompanying them and some were shown being taught how to drive by their husbands.

The protest was adopted by many influential Saudi figures, including Madiha Al Ajroush, prominent Saudi activist and psychotherapist, activist and university professor Aziza Youssef and women’s rights leading activist who prompted the 2011 driving protest and was arrested in the aftermath, Manal Al sharif.

“I love the support and I am proud of the empowerment our women are feeling and even more proud of those men supporting the right for women to drive,” says Komsany.

Many Saudi men have also publicly supported the cause of the campaign, with comedian Hisham Fageeh making a satirical song, No Women No Drive, that quickly went viral. “Say I remember, when you used to sit, in the family car but backseat. Ovaries safe and well, so you can make lots and lots of babies,” making fun of a conservative clergyman who stated driving is banned because it poses danger on women’s ovaries.

In the short film, the comedian Hisham Fageeh sings, whistles and dances. The lyrics include: “I remember when you used to sit in the family car but backseat … in this bright future you can’t forget your past, so put your car key away”.

Wary support

Although many women believed and called for their right to drive, many worried about prosecution, reactions from the family and possible repercussion and opted not to participate in the campaign. Others did not participate because they either do not believe this is the right way to snatch their rights or because they believe more pressing issues need to be dealt with.

Five women in their 20’s expressed their support for the October 26th cause but didn’t want to take the risk and their parents wouldn’t approve.

“Honestly, knowing what they have done to women before, I [wouldn’t’] participate,” says Rabaa Abu-Botain, assistant lecturer, who was in Egypt at the time of the protest. “If I had wanted to participate I know my family would have objected. Family names are taboos in Saudi so if I do anything to mess the reputation of the family name it would be unacceptable.”

Aboud also expresses her doubts about the timing of the campaign in a society like Saudi. “Saudi society deals with its customs and traditions with huge sacredness so what goes for Egypt or any other country doesn’t necessarily [work] for Saudi,” she says. “Matters here are not solved by rebellious acts. Saudi is different and there are other important and pressing issues, like health, unemployment and education.”

Aboud also worries about the possible international repercussions of this campaign and expresses her refusal of a women’s rights issue like driving being used to “threaten my country’s stability, given the [current events] I fear it is a chance for enemies to use it to their benefit.”

No Place for Women to Drive

Despite the virtual support for the campaign by men and women inside and outside of the Kingdom, many Saudi men and women still believe it’s not the right time for women to be driving in the streets of Saudi.

Two of the Saudi women we interviewed believed Saudi women shouldn’t be allowed to drive, both were in their late 20’s and early 30‘s.

“I do not support this initiative at the time being because I feel that it’s still too early for it,” says Duaa Fadul, a 24-year-old dentist. “There are many wrong attitudes from men that need to be fixed and then we can progress bit by bit. If they approve women’s driving now there will be a lot of issues […] there is a lot of deviant behaviour as is.”

Fadul adds that she is getting harassed by people in the street with the driver behind the wheel, so the harassment would be so much worse with her behind the wheel. “Should I throw myself in danger and make my family worry all the time?” she adds.

For Fadul, there are many more pressing issues than driving that women should fight for, and these include divorcees and widows rights. She insists that this is not the way to demand one’s rights.

Gentle Nudging

Sixteen women were fined for breaking the law but none, however, were arrested. The ministry of interior had previous issued warnings against Saturday’s calls, insisting women driving is banned under the law and any defiance will face prosecution but hasn’t specified the action to be taken against those defying the ban. Campaign activist Zaki Safar told the BBC that the ministry of interior’s statement was “an unusually explicit statement of the ban” as no articles under Saudi law prevents women from driving. The BBC also stated having received a document that details to policemen how to handle women drivers; issuing them and their ‘male guardians’ a warning, making them sign a promise not to drive again and giving the car keys to the male guardian.

This is not, however, the first time a similar initiative takes place, it is the third of its kind since 1995 when 50 women participating faced arrests and even loss of their jobs. The second protest took place in 2011 when 40 women took the wheels of their cars and a Saudi journalist was arrested after posting a video of herself driving. Many officials, however, and many members of the royal family are inclined towards lifting the ban but still receive heavy criticism from conservative statesmen and clergymen.

“It reminds me of Rosa Parks: That moment she decided to get on that bus and sit, she sat for a cause. She sat knowing that her sitting will change the future, we live for that hope,” concludes Komsany.

Submit a Comment